|

The Vedutismo Tradition

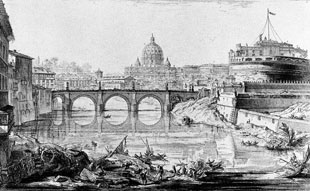

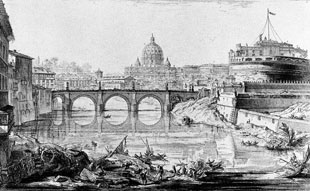

Veduta del Tevere a Castel Sant'Angelo, G. Vanvitelli, 1720

Plate 86, Ponte Sant Angelo, Giuseppe Vasi, 1744.

Vedute del Ponte and Castello Sant'Angelo, G.B. Piranesi,

1750

The Grand Tour may not have created the vedutisti but it did facilitate the economic and cultural atmosphere in which they thrived, increasing the demand for their wares and providing a means for dissemination to other European capitals. Before the journey the vedute served as a visual enticement, depicting sites for the traveler with increasing realism. Upon returning home the vedute functioned as a memento recalling the splendors visited and acted as incentive for others to likewise to embark on their own adventure.

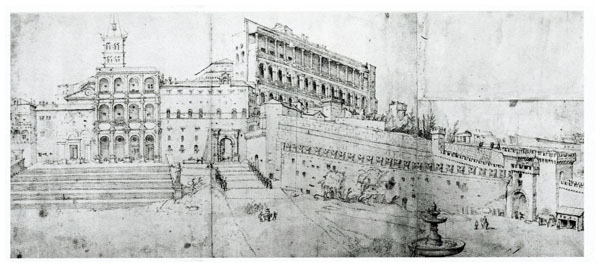

Pianta di Roma, Alessandro Strozzi, 1474.

Early Roman Vedute

Topographic chroniclers who visited Rome in the 16th century portrayed the city with increasing accuracy and detail, using scientific perspective as a guide to capture their impressions. The emergence of the vedute or realistic city views replaced the medieval tendency to see the city in symbolic and often fanciful terms as epitomized by the medieval Mirabilia Urbis Romae from about 1150 and in its numerous reincarnations. These later artists constructed accurate drawings of ancient ruins as well as contemporary religious and secular works of architecture of their day, and in so doing left a valuable legacy of the their times and customs.

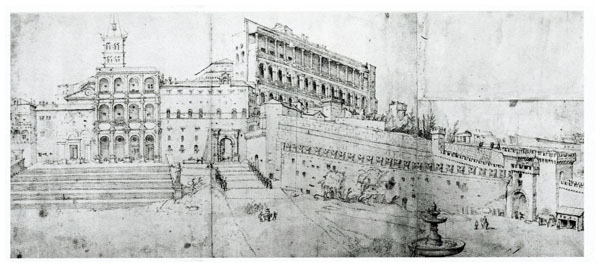

S. Pietro e le Logge Vaticane, M. van Heemskerck, 1533

The genre first became popular in the north where realistic scenes of both landscapes and cityscapes were created by 16th century artists in the Low Countries. Visiting artists who traveled across the Alps such as Martin van Heemskerck (1498-1574) carried this tradition to Rome. Heemskerck was not content to show important buildings as isolated objects but made a point of showing them in their surrounding urban context as well. Conceiving architecture within its urban setting is the fundamental principle of the vedute and explains why this tradition continues to have special significance for the study of architecture and urbanism as a phenomenon inextricably linked to place. For example, Heemskerck’s drawing of St. Peter’s as the nominal subject shows nearby ordinary structures as an integral part of the scene. This practice could also document the life of the city portraying its citizens on special occasions or capturing their daily activities, sometimes revealing the life of the city with a surprisingly candid eye. Likewise other artists who provided views of the Rome (significantly almost all from abroad) like Stefano Duperac (1525 ca.-1604) and Israel Silvestre (1621-1691) each of whom made significant contributions within this tradition so that by the end of the 17th century it was a well established genre among visiting and Roman artists.

|

|

| Villa Panphilj, Giovanni Battista Falda, ca. 1670-75 |

Plate 200. Villa e Casino Panphilj, Giuseppe Vasi, 1761 |

Giovanni Battista Falda (1643-1678)

Artists working within this pictorial tradition in the late 17th century such as Lievin Cruyl (1634 -1720 ca.) and Giovanni Battista Falda (1643- 1678) established a repertory of views for documenting Rome that would set the stage for later artists. Falda was the first notable vedutista working in this tradition as a print maker who helped elevate the engraved print and work on paper as equal to the painted canvas in terms of its artistic significance. During his brief but prolific career he demonstrated an extraordinary capacity to capture the city view accurately and in vivid detail. Falda’s work was a great commercial success because of the multiple prints which a single matrice or copper plate could produce. Falda concentrated on cityscapes and landscapes on paper that were avidly sought after by the Grand Tourist and were master works in their own right.

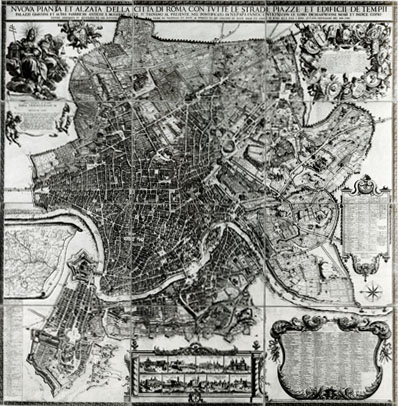

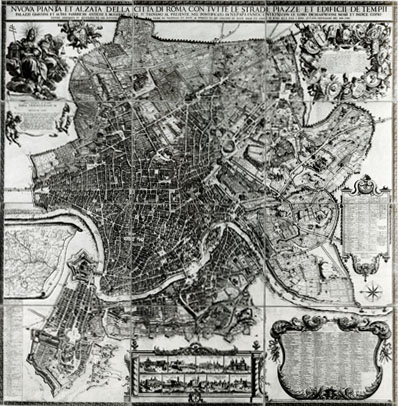

Pianta di Roma, Giovanni Battista Falda, 1676

Falda’s interest in capturing the topography of the city eventually included his attempt to combine both plan and pictorial view. His masterful 1676 axonometric plan (paraline drawing whereby parallel lines remain parallel) of Rome is really a hybridized form of the ichnographic plan and pictorial view. The plan projection drawing used by Falda here and also in his book on the villas and gardens of Rome is not a true perspective but rather a plan projection view at 45 degrees which simulates three dimensions without employing vanishing points, diminution in size or converging lines. The more common related pictorial views which bridge the gap with varying degrees of success between the two modes of description is the volo d’uccello or bird's eye view.

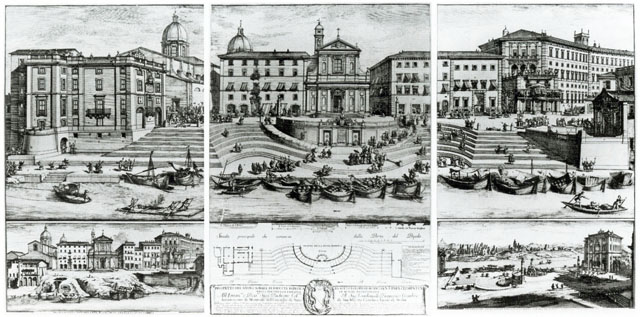

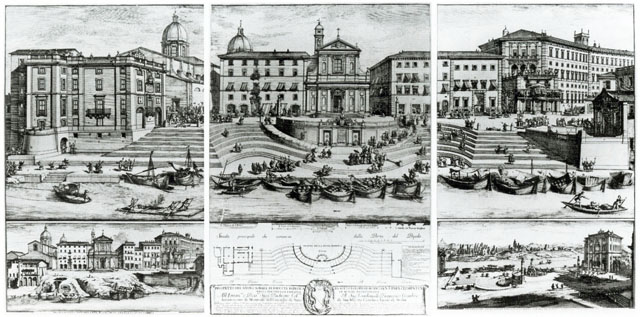

Porto di Ripetta, Specchi,

Alessandro Specchi (1668-1729)

Trained as an architect, Specchi provides another highly instructive and synthetic method for representing the city. In his View of the Porto di Ripetta from 1704 (he designed the complex which he depicts in 1703) he presents an enlarged frontal view of the famous water piazza. He also provides pendant views at either side which show a view from the piazza looking toward Prati and another which reveals the earlier state of the site before his intervention. Finally he centers a plan view of the river port, surrounded by the accompanying pictorial views. These multiple views, both pictorial and planimetric, round out a thorough documentation of his masterpiece and most likely inspired future vedutisti such as Piranesi who was accomplished in both modes of representation as well.

|

|

| Il Tevere e il ponte Rotto dall'Aventino, Vanvitelli, 1682 |

Plate 94a, Ponte Rotto, Giuseppe Vasi, 1754 |

Gaspar van Wittel (Vanvitelli) (1652/53-1736)

Vanvitelli is said to have invented the photographically realistic view and is reputed to have used a camera obscura, a box-like optical device which employs a reflective mirror and lens, to draw his scenes. Not content to merely represent buildings and landscapes in a vacuum, Vanvitelli included stunning atmospheric and lighting effects as well as entourage (secondary supporting elements of a scene such as persons, animals, fowl, conveyances, and other landscape elements including ) shown in minute detail. In particular, his views of the Tiber had a direct impact on Giuseppe Vasi’s vedute of the same subject (Book V of the Magnificenze from 1747, an earlier edition being published separately in 1744).

|

|

| Galleria di vedute di Roma moderna, G.P. Panini, 1759 |

Galleria di vedute di Roma Antica, G.P. Panini, 1758 |

Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765)

A painter of the next generation, Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691-1765), composed large scale canvases of topographic views of the city that carried this realism forward with increasingly vivid depictions of dozens of places in the city typically incorporating a strong social component by depicting festivals as well as daily life in the city. Panini developed an eye for the picturesque quality of ruins which punctuated the Roman countryside and also at its center. Using the capriccio (being a branch of the larger vedutista genre) he developed the then popular conceit of the moveable monument or the imaginary landscape whereby the artist composed actual buildings in fanciful but plausible topographic arrangements to evoke Rome’s past splendors. Simultaneously he celebrated the city’s rebirth under the popes by representing modern urban renewal projects. His two most famous canvases, Roma Antica and Roma Moderna are pendants which contrive to show the most important views of the city as a collection of his own paintings hung in an imaginary salon—a kind of trophy room--staged to include a variety of sculpture and other artifacts by both ancient and modern artists. Roma Antica (1758) shows the Pantheon, Arch of Constantine, the Coliseum, and the Basilica of Maxentius among others. Roma Moderna (1759) depicts the Piazza Navona, S. Ivo, the Campidoglio and includes the Spanish Steps (completed in 1730) and the Trevi Fountain (completed after the painting 1762). This up to date, even anticipatory quality of the painting making it almost journalistic in nature. Panini completes the ensemble with two portraits, himself and patron (no doubt a veteran of the Grand Tour) and members of their respective entourages. These paintings sum up the Grand Tour and the riches it might bestow on the sophisticated traveler.

The Venetian Connection

Venice in the 18th century was home to a trio of great vedutisti, the most famous being Canaletto (1697-1768) whose scenes of La Serenissima helped promote that city as a major destination for the Grand Tour. Francesco Guardi (1712-1793) and the itinerant Bernardo Bellotto (1720-1780), Canaletto’s nephew, continued the brilliance of his cityscapes. The latter practiced in Dresden, Warsaw as well as in Rome. It was Piranesi, a Venetian by birth, who picked up this painterly tradition of light and space and carried it with him to Rome. After working in Vasi’s studio briefly he set out on his own combining the knowledge of Roman monuments he most likely gained from Vasi with the chiaroscuro techniques of the Venetian school creating some of the most hauntingly vivid scenes of Rome ever produced.

|

|

| Piazza Navona, Giovanni Battista Falda, 1677 |

Plate 26. Piazza Navona, Giuseppe Vasi, 1752 |

Vasi and Vedutismo

It is into this artistic context of vedutismo established by a string of great artists and fueled by the enormous popularity of the genre that Giuseppe Vasi’s work should be placed. He benefited greatly from the vedute tradition in two important ways. First the vedutisti of Rome established a repertory of significant sites in the city and, in more than one case, provided specific compositions that would later be taken up by Vasi. Falda’s etching of the Prospetto della Nobil’ Piazza Navona, 1677, relates closely to Vasi’s later view of the same piazza, Plate 26, from the Magnificenze.

|

|

| Veduta of Castel S'Angelo, Vanvitelli, ca. 1720 |

Plate 86. Ponte Adriano oggi detto S. Angelo, Vasi, 1754 |

Vanvitelli’s veduta of Castel S’Angelo, ca. 1720, provides another early example which should be paired with Vasi’s almost identical view of, Plate 86, from the same ten volumes. Second, the vedutisti established a taste for the city view that made it possible for Vasi to win powerful patronage, so that even though he was relatively unproven at the time of his arrival in Rome his expertise in this genre won the support of the Farnese which allowed him to pursue his passion for recording the city throughout his career. This coupled with the seemingly endless train of visitors to the city anxious to capture a fitting memento of their visit with which to return home to both recall and advertise their experiences in Rome, provided a fertile environment in which he could flourish, both aesthetically and commercially.

|